The End I Expected

When I moved back home in August 2024, I assumed my time at Amazon was coming to an end. I’d left my assigned office in Denver, accepting I’d fall out of RTO (return-to-office) compliance, ready to face the consequences. The cumulative weight of two years of re-orgs, a high-churn team, chaotic projects, multiple rounds of layoffs, and an ever-shifting RTO policy had taken a toll. My ambition had carried me through a promotion, then flat-lined shortly after. I was done.

I’d already spent a year convincing myself that I should stay in Denver. In reality, I was living somewhere I no longer wanted to live, taking Zoom calls from a lonely office co-located with exactly 0 teammates, solely to comply with a corporate mandate. My continued compliance felt like a rejection of my agency - a never-explicitly-made decision to allow my entire life to be shaped around the satisfaction of a shifting metric.

There were two options: quit or move again. I wasn’t going back to Denver and I didn’t have another cross-country move in me - not for Amazon at least. So I bought myself some time to make the decision by taking a seven-week leave, hoping the trip would grant me clarity - and then conviction in choosing a path. It didn’t.

Instead, upon my return, I found a way to postpone having to decide at all. I met with a nearby subsidiary’s building manager, expecting nothing more than a “Sorry, can’t help ya”, but left with permanent access to a space I technically wasn’t allowed to use, granted under an explicit “If anyone asks, it wasn’t me.” So, I carried on, expecting that my office access (and employment) would last a few months max - until someone inevitably noticed and made the decision I couldn’t.

A Year of Not Deciding

What followed has been 15 months of no-one noticing, or rather caring - and my settling into a suburban Philly routine. What was intended to be a chance to catch my breath turned into…well…my life. 5 days a week, I wake up way too early, work a few hours, pull on my tattered, decade-old grey sweatpants and crocs, and do a mandatory commute to an office where no one knows who I am. I say what’s up to the security guards, tap my badge against the badge reader, hold the door ajar, reach in, then tap again on the other side. Take that, HR!

The most human part of my day comes right after. I take the dogs to the woods where I let them drift off-leash…Scooby plunging into the water, Chase jealously watching from the creek bank, offended he didn’t think of it first.

I feel like my mind should go quiet - time in nature and all that. Instead, my mind stays at work…turning over lines of code I should definitely fix when I get home, re-prioritizing items on a never-ending checklist, rehashing design decisions and their implications. In those moments, I wish I could just decide “no more!” and erase work from my consciousness. Something Severance-esque. My attention snaps back to reality when I notice the dogs snacking on a deer carcass. “Chase! ScoooBEE! Noooo!”

On my best days, I love coding. It’s so gratifying - tuning out the world, going deep into a problem, iterating over and over until an elegant solution emerges - a natural curiosity driving an effortless flow. Yet there’s an undercurrent of futility. An ever-expanding ecosystem of messy complexity overshadows the win I was momentarily stoked about. I tune back in, take in the whole system, the backlog, the upcoming projects, the politics that govern it all, and just think…fuck.

I’ve seen enough failed projects touted as successes and metrics bent beyond recognition to know that even IF what I’ve built delivers real value, it’s likely to be lost among a sea of half-truths sold for the sake of optics, then sunk by the continued piling of tech debt on a surprisingly-still-afloat ship.

I realize it sounds like I’ve inadvertently built my life around something I loathe - a toxic relationship - but really the job itself is fine. Year three, while not “great”, was better than years one and two. Great compensation, interesting problems, talented coworkers, and ample learning opportunities convince me it makes sense to stick around for year four.

But string together enough of these years and the future looks bleak. While these years have grown me into an engineer, I can’t ignore a shift in my mindset. A loss aversion has crept in…a guarding of a careful stasis, fed by work and the comforts of home, that keeps me from asking for more, from testing whether life could be bigger than this.

Over the summer, I sat across from a dermatologist as he prescribed a heavy-duty immune-modulating drug. He walked through the potential side effects: weight loss, depression. I told him my condition had been stable for nearly a decade before starting this job - then it progressively worsened.

“For about 90% of my patients a flare coincides with a stressful period”, he said dispassionately.

I paused, waiting for something…advice, concern, an alternative. Instead, when I mentioned I’d thought about leaving my job, he shrugged.

“Most people can’t just quit their jobs.”

There it was! The universality of the trade that many of us make, an almost-inevitable decision to sacrifice health for work. I notice it in my body: in the angry eruptions on my skin, nights of fractured sleep, and a low-grade pressure that never fully lifts. And in my soul: the growing year-count of the FAANG stamp of approval on my résumé and a lone upward-sloping line in my brokerage account - both crowding out a higher purpose.

How the Fire Died

If I’m being honest, when I got the call that Amazon was moving forward with an offer, compensation was a primary factor in joining. I knew the reputation. Everyone in tech knows Amazon can be brutal. But I had a great feeling about my would-be manager. And I was excited to work on a greenfield project with talented engineers. Even if it went horribly, the experience would crack open possibility. The future felt expansive.

Somewhere along the way, the fire went out and the potential futures I’d imagined narrowed, and by last summer, when I set out to find a new job, I felt a total absence of enthusiasm. As I dragged myself through interviews, it became undeniable: I had no excitement left for a future in software. Maybe that’s a natural plateau as you settle into a career. Or maybe that’s what happens when you stay too long inside a cutthroat culture that unapologetically reduces you to a number.

Maybe I should’ve paid closer attention to what happened in my first ten months: by then I was on my 3rd manager, 2nd re-org, 2 of my original teammates had been managed out, Amazon had laid off 27,000 employees and declared remote work was no longer chill. At the time, each disruption felt survivable. I put my head down, focused on what I could control, and still managed to enjoy the technical work. Regardless of the chaos, staying made sense. I didn’t exactly have options as a junior engineer in a cratering job market.

At some point, inertia and prudence started to blur, and with them my sense of choice. I couldn’t tell anymore whether the market had taken my options away…or whether I had simply learned to accept staying as normal. Nor could I tell whether to trust the bubbling suspicion that staying was really just a way of postponing risk, the discomfort of change, and the giving up of the familiar, in exchange for a future I couldn’t yet picture.

Flagged

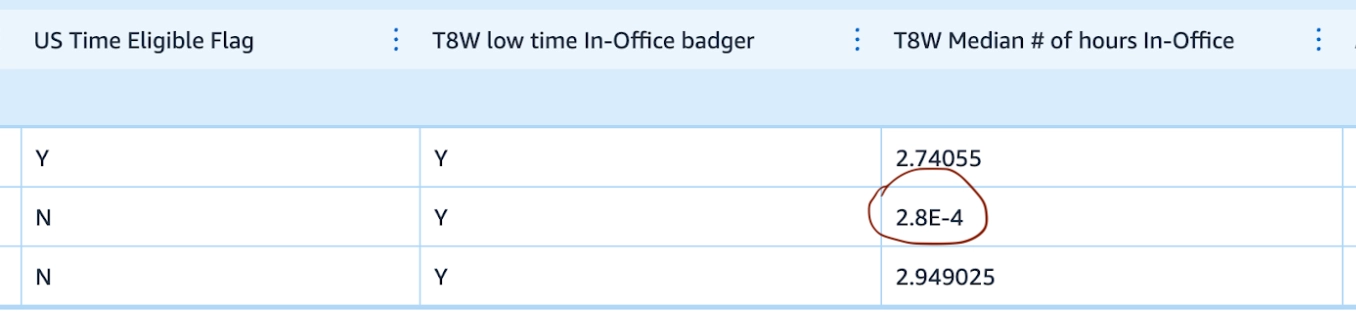

15 months after I found the loophole that let me stay without choosing, I was finally flagged for RTO non-compliance. Not because I wasn’t showing up 5 days a week, but because my average time in-office was under 4 hours a day - a brand new, unwritten and unannounced policy.

My manager sent me a screenshot. A table titled “Low-time badger employees” with my name in the left-most column and another column titled “T8W Median # of hours-In-Office” with a value of 2.8e-4. I did the math. I’m falling short…by about…3 hours, 59 minutes, and 58.99 seconds.

I don’t know what comes next. Do I comply…and go back to sitting in a lonely office, counting down the 4 hours and 1 minute until my release, yielding my agency, cementing my life of suburban stagnation? How long can I really keep drifting in this administrative gray zone?

And if I do comply…what am I actually doing? By “not choosing”, I’ve actually been choosing all along: choosing the familiar, choosing the safe slope of the line, choosing to let systems and numbers dictate the shape of my life. Hours and days and years tick by regardless. The only open question is whether I’m willing to keep calling this drift…or finally call it what it’s always been: a choice.